For Goan Catholics

Many things come to mind when you think of Pakistan. Religious strife. Benazir Bhutto. The Taliban. Military rule. The ghazal and the qawwali. But Goan Catholics? Indeed there was a time when migrating to Karachi, Pakistan seemed like just the thing to do for Goans in search of a better life. Call up Google maps, advice and you’ll see Karachi is not terribly far from Goa, just further up from Gujarat and not even as far as, say, New Delhi. Roman Catholic Goans in Karachi today number between 12,000 and 13,000 people, and they remain one of the most cohesive and fascinating communities comprising Pakistan’s 2.8 million Christians (about 1.6 percent of the country’s population). Below, author, columnist and Goa Diaspora expert Selma Carvalho gives us a brief history of the Goan community of Pakistan.

| Nothing fascinates me more than turn-of-the-century Goan history for the sheer audacity, perseverance and intellectual vibrancy of its intrepid migrations. It is not a coincidence that the new arrivals went about doggedly building Catholic churches and parochial schools, for it is European Catholicism which ironically broke the stranglehold of the communal and replaced it with individualism, enabling migration. Driven by self-interest, Goans would venture far; the concept of community would no longer be bound to geography. Much like the Jewish diaspora, it would be held together by abstract notions of religion, culture and a curious Anglicisation. |

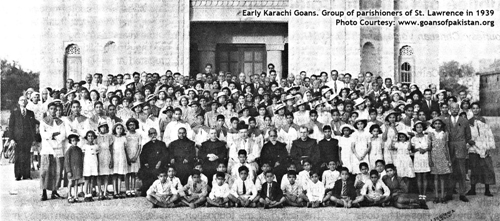

From Karachi comes a fascinating book, The Origin and Evolution of St. Lawrence’s Parish by Oswin Mascarenhas, which sheds light on the Goan migration to Pakistan, and the formation of Cincinnatus town and St. Lawrence’s parish. The Karachi diaspora predates that of East Africa by a good fifty years. By 1858, when Goans were just venturing into Zanzibar, the J. C Misquita bakery was already thriving at Saddar. The importance of Catholic bakeries and butcheries cannot be underestimated; they acted as general contractors for flour, bread, beef, vegetables and provisions to English settlements and cantonments. In a very real sense, they were the vanguard of Goan migration. Eventually, every venture in the diaspora, be it the Goan club or the Goan business, was intimately linked to the Catholic church, thus creating a overlapping history.

Mascarenhas traces the Goan settlement of what was then the Sindh to Sir Charles Napier, the beleaguered English general who, in 1842, had the unfortunate task of quelling rebellions on the northern frontier. ‘Accompanying the army,’ writes Mascarenhas, ‘were civilian officers and camp followers many of whom were also Catholic.’ This assumption bears out. The English were particularly fond of Goans as personal valets, given their ability to speak a smattering of languages. Sir Richard Burton, part of Napier’s contingent, tells us he started his army life in India with just ‘Salvador Soares, a handsome Goanese; a horse, in the shape of a dun-coloured Kattywar nag; a horsekeeper, a dog, a tent.’ But camp followers were not just made up of menials, for army personnel also needed medical and pastoral care. Goan doctors and priests attended to them in the most austere and perilous of places.

By Mascarenhas’s account, mid-nineteenth century Karachi, then a bustling port and city, had about 2000 Catholics, flourishing under British patronage. A spry and moderately affluent class of entrepreneurs, doctors and mid-level government employees emerged, allowing them to invest in private property. In February 1906, three gentlemen, A. N. Menezes, an engineer by profession, D. F. Faria and Caciano Villa Reis visited a piggery in the Garden Quarters, which belonged to a P. J. D’Mello. They found the adjoining land was up for sale. This was the genesis of what erroneously came to be known as Cincinnatus town after one Cincinnatus F. D’Abreo, who at the time was the assistant collector of customs. Although he was actively involved in the colonisation scheme, he had neither planned it nor conceived of it.

Mascarenhas offers no compelling reason as to why a largely urban community would want to leave the cantonment area and take up residence on its outskirts, other than to seek more salubrious conditions. But perhaps a parallel can be drawn with similar planned ‘colonisations’, model towns or residential quarters, which the British encouraged in other parts of the empire, in the early 1900s, which effectively segregated populations. Cincinnatus town grew to be the abode of the moneyed, professional class who took pride in their homes; they ‘kept poultry and tended their gardens where they grew fruit trees and sowed beds of flowers.’

What’s interesting, is not just the cross-cultural exchanges that took place as a result of Goan migration but the very tangible manner in which Goans influenced the architectural landscape and husbandry of alien lands. Mascarenhas tells us that Goans of Pakistan kept in touch with ‘their roots in Goa,’ and on visits there brought back ‘seedlings and grafts.’ Their gardens bloomed with flowers and fruits like bananas, chikoos and custard-apples.

It might seem strange to us now, given Pakistan’s conflicted contemporary history, the grim reality of its sectarian strife and the marginalisation of minority religions, that Goans opted to live in Pakistan post-independence. But there was a moment there, through the forties and fifties, when hope reigned, when businesses surged, and Catholics streamed in. Goans, literate and urbanised, took up positions in the newly formed government offices of this emerging nation; women joined the workforce, sometimes earning more than their husbands. The quiet sobriety of Christian values meant the Goan community continued doing what it had done best: tending to the disadvantaged, and building stellar educational and health care facilities.

Pakistan’s Christian population has held steady for the past two decades at about 2.8 million people, but many of them feel alienated in a nation that has become increasingly theocratic. Karachi has five Goan-majority churches, and while the Goan population is now somewhat lower than its estimated peak of 15,000, the community’s numbers are more or less holding. As important, its members remain vibrant and hopeful. Their contributions to life in Karachi are unmistakable, even if too few of their countrymen see it.

___

Selma Carvalho is a columnist and author of ‘A Railway Runs Through: Goans of British East Africa, 1865-1980’. Between 2011-2014, she headed the Oral Histories of British-Goans project.